-story about mercha chfula at the VERY END of Matot

-munach which has effect from yerach ben yomo, yerach ben yomo itself, karnei fara (only other time any of these appear in Bible is in 7th Chapter of Megilat Esther, but you never notice it because it is part of the name of Haman, the recitation of which we stamp out

-Journeys (“Shirat HaYam”) trop is read by many on some of the verses of the Journeys, including the one about going through the Sea of Reeds and anywhere else where an especially notable miracle happened

-Sof Sefer: We end the seventh aliyah with the special trop that ends each of the five books of the Torah.

If you are a regular reader of my Divrei Torah, you know my obsession with oddities in the text, including rare trop, or cantillation. Well, this week we have hit the mother lode! This week there are SIX different rare trops in the joint torah portions of Matot and Masei. Making sense of why the particular sections contain these rare tropes, well, תיק"ו

(though there are no dots…)

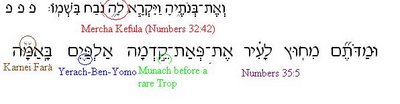

The first of these rare trops (keep count at home, kids), a Mercha Kfula (which looks like two commas) is found at the very end of our first parasha. I found this out the hard way a couple of years ago. I read that there was a mercha kefula (literally “double mercha”) in the Parasha Matot. I decided to look for it and looked through the entire torah portion, 3 chapters, and finally found it on the penpenultimate word. Oh well.

We next revisit the special trop we used at Shirat HaYam, the Song at the Sea of Reeds we had in Parashat Beshalach in Exodus, when we recite the names of places on our journey where especially miraculous events occurred, including the Sea of Reeds itself.

Next we have three in a row. Yerach Ben Yomo, Karnei Fara, and the Munach that precedes the Yerach ben Yomo. A call munach the wildcard trope because its melody changes depending on whatever trop follows it. Since the Yerach Ben Yomo only occurs once in the Torah, I consider the sound that the munach makes here significant enough to call it a rare trop. Yerach Ben Yomo means a day-old moon, meaning the first crescent you see of the new moon. I guess the symbol for it could be considered as sort of a moon crescent. Practically, it is an upside down etnachta and it sounds exactly like how I do Sof Aliyah on the High Holidays. Karnei Fara, Cow Horns, follow, also in its only appearance in the Torah, and guess what, it looks like cow horns! Everyone that does it tries to make it up because nobody actually knows it because nobody actually learns it. When I learned trop, the only rare trop I was taught was Shalshelet, which, incidentally, is the only rare trop not in these parshiot. Anyway, the only other time these three trops appear in Bible is in the 7th Chapter of Megilat Esther, but you never notice it because it is used during the name of Haman, the recitation of which we stamp out.

So that’s five. The sixth rare trop here, only seen five times in the Torah, is Sof Sefer, the special ending we do for the seventh aliyah that ends a book of the Torah (which is then followed by Chazak Chazak V’Nitchazek!)

Alright, now to the real stuff. At the end of these parshiot, we are effectively at the end of the journey to the Promised Land. The book of Deuteronomy is basically a retelling (it is Greek for “second telling”) of the three center books of the Torah, so it effectively ends here. However, there seems to be a genre transition, whereas the book of Deuteronomy seems to be the exclusively “morally ethical” book of the torah, we see shades of that here, in two particular examples: A very intriguing story faces us within these final parshiot which can teach us a lot about solving collective action problems (a political science term, look it up). The people are about to cross over the Jordan to begin to take the land (which won’t actually happen until the Book of Joshua). The tribes of Reuven, Gad, and half of Menashe see the beautiful land they conquered from Sichon, king of the Amorites and Og, king of Bashan on the East Bank of the Jordan, a land good for grazing cattle, and they want to settle down there. Moses gets angry that they are ditching and they have an argument. A great compromise is reached. They will inherit the land, and their wives and children can stay there, but the men must participate in the fight against the Canaanites and only after all the land in Canaan is conquered can they return to their homes, the East Bank shall be these 2 ½ tribes’ inheritance.

Second we have the Arei Miklat, the cities of refuge. If one accidentially (and only accidentially) killed someone (for example if someone is swinging an axe and the axe-head flies off the handle, striking and killing someone), then they can flee to one of these six cities, three on each side of the Jordan (the answer to the previous issue of whether or not the 2 ½ tribes can settle in Transjordan is once again in the affirmative) and are safe from goalei-dam, blood-avengers, family members of the person who you accidentally slew who in ancient societies had the right to vigilante justice. For as long as the accidental manslaughter-er stays in the clearly marked city, he is safe from bounty-hunters, but if he steps out, he’s fair game. Once the High Priest dies, he is home-free and nobody is allowed to touch him for this matter. Last summer on a literally lightning-packed Friday, I created a game of Ir Miklat which was basically a game of tag with six hula-hoops as Irei miklat. We had to move it indoors when the field was struck by lightning. Anyway, this gives people the chance to remain alive when they didn’t mean another person harm. It should be noted that in second temple times the Irei Miklat were no longer voluntary cities of refuge but instead prison cities which had the added feature of protecting the rest of the citizens from the dangerous criminals.

This is running long so I’m going to stop.

Chazak Chazak V’Nitchazek!

No comments:

Post a Comment