We now arrive at Tisha B'Av, the Saddest day of the year, our mourning (in reverse of regular mourning ritual) getting more and more severe. On Tisha B'Av we famously ask "Eicha?!" "How?!" (the Hebrew title of the Book of Lamentations).

That can easily be found out by doing a little research. The question I want to ask is not "Eicha?!" but "Lama?!" "Why?!".

There are three cardinal sins in Judaism that are so heinous, that one is supposed to forfeit their life instead of violating one of these three. It’s a mitzvah and there is even a prayer you say before you are killed (“Al Kiddush Hashem”, “Upon the Sanctification of The Name [of God]). These sins are Murder, Idolatry, and Sexual Taboos (a list can be found in Leviticus 22 and is the Torah Reading for the afternoon of Yom Kippur). The First Temple was Destroyed because of flagrant and constant violations of these three sins by the Jewish people. People were much better, apparently, during the Second Temple times, and the Jews were much more dedicated to God (who had proven that though the Jews would never be wiped out (Covenant with Abraham and Promise to Moses), pissing Him off would not be tolerated), yet it was for one other sin that the Second Temple was Destroyed and a much longer, much harsher Exile occurred (and technically and according to many still continues to this day). What could be worse than Murder? What could anger God more than defying His Laws? Sinat Chinam, Causeless, free-flowing, hatred was the reason the second temple was destroyed. Case in point is the famous story of Kamsa and Bar-Kamsa, a Tisha B’Av classic (which also has been my saving grace on getting kids through the day on Tisha B’Av at camp, though everyone also uses it). I present a version that I found on the Internet at

The Story of Kamsa and Bar Kamsa

The Jewish Magazine

The Legend from the Talmud explaining the reasons for the destruction of the TempleIn the Talmud, there is a story which relates to us how the sages understood the causes of the destruction of the Temple and our expulsion into the Diaspora. It is called the story of Kamsa and Bar Kamsa.

Because of Kamsa and Bar Kamsa, two different people, Jerusalem was destroyed. There was a man who was very good friends with Kamsa and did not get along with another person with a similar name, Bar Kamsa. One time this man made a large banquet and told his servant to invite his friend Kamsa. The servant made a mistake and invited Bar Kamsa.

When the man came to his banquet, he was surprised to see Bar Kamsa sitting there. Not wanting to see his enemy benefiting from his meal, he ordered him to leave. Bar Kamsa, not wanting to be embarrassed, offered to pay for his portion of food. The man refused to accept compensation, and ordered Bar Kamsa to leave.

Bar Kamsa, still not wanting to be embarrassed, offered to pay for half of the expenses of the large banquet. Still the man refused and ordered Bar Kamsa to leave. Finally, Bar Kamsa offered to pay for the entire banquet. In anger, the man grabbed Bar Kamsa with his own hands and physically ejected Bar Kamsa from the banquet.

Bar Kamsa said that since there were many Rabbis at the meal and none of them objected to the outrageous behavior on the part of the host, it must be that the Rabbis agreed with this embarrassing episode. Bar Kamsa decided to fix them all. He went to speak with the Caesar (the king of Rome) and told him that the Jews are planning a rebellion against the Romans.

The Roman Caesar did not believe it. Bar Kamsa told him to send a sacrifice to the Temple in Jerusalem and see if the Jews will bring it on to the Altar. The Caesar agreed and sent an animal. On the way to Jerusalem, Bar Kamsa inflicted a minor wound into the lip (or eye) of the animal, so small that by almost all standards it would not be considered a blemish.

When the animal arrived in the Temple in Jerusalem, the Rabbis examined the animal and saw the tiny blemish. They didn't know what to do. Although according to Jewish law it was forbidden to offer such an animal on the Altar, they reasoned that not to offer it for such a minor reason could endanger themselves and cause a breach with the Caesar. Therefore they wanted to have the animal brought up upon the Altar. Rabbi Zacharia ben Avkolus however disagreed fearing that people will learn from this that animals with blemishes may be brought upon the Altar.

The Rabbis then thought to have Bar Kamsa killed in order that word not be brought back to the Caesar. Rabbi Zacharia ben Avkolus again disagreed, fearing that people may think that one who brings an animal with a blemish can be put to death.

Rabbi Yochanan at this point taught that due to the extreme piety of Rabbi Zacharia ben Avkolus, the Temple was destroyed, the Sanctuary burnt in flames and we were exiled from our land.

This is one of the stories in the Talmud, the rest is history. What we need to do is to analyze this story to understand what the sages were trying to convey in the story.

First, we can note that the combined incidences of the host of the banquet and Bar Kamsa showed a tremendous lack of feelings for the welfare of another. From this we learn the importance of putting other peoples feelings ahead of our desires. Still, this does not compare to the lack of action on the part of the assembled Rabbis at the banquet, who, had they protested the lack of consideration, could have averted a national tragedy.

We learn from this the awesome responsibilities of those people who are in positions of leadership and influence. Yet even more so, is the blame on the shoulders of Rabbi Zacharia ben Avkolus, because of his great piety, not only was the Temple and Jerusalem destroyed, but we were exiled through out the nations. Rabbi Zacharia ben Avkolus who was the leader and most influential man in his generation should have seen the results of his actions. National leaders must know when to stand firm and when and how to bend, to avoid disastrous results. He must be able to put his own personal agenda and feelings aside and make proper decisions.

May we all learn from this chilling episode in our Jewish History, that our behavior is of extreme importance. May we, through the good will and cheerful help that we are able to give to another fellow Jew, see the rebuilding of the Temple swiftly in our days.

Many compare Tisha B’Av to Yom Kippur, but I feel that their purposes are much better served contrasted. On the surface they may seem alike and it is true that they are the only two major fasts, those that last around 25 hours and hold increased restrictions, but they couldn’t be more different. Tisha B’Av is sometimes known as the Black Fast, is obsessed with punishment, and from sunset to mid-day the gates of heaven are completely closed to prayer. Yom Kippur, on the other hand, the White Fast, is focused on forgiveness and atonement, and this date marks one of the greatest events in History and the day which will forever be the one where the gates of heaven are completely open to all who seek forgiveness. The Torah says of Yom Kippur, "כי ביום הזה יכפר עליכם לטהר אתכם מכל חטאתכם לפני ה' תתהרו"

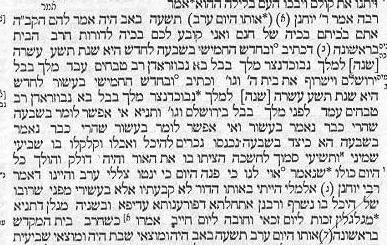

, “that on this day will be atoned for yourselves, purifying y’all of all your sins, before God you shall be pure.” (Leviticus 16:30). As for the 9th of Av, according to tradition the evening of which Ten Spies brought a negative report about the inhabitants of the land of Canaan, (which I have previously discussed in my remarks on Parashat Shlach Lecha. I include the text from Taanit 29a where, among other items which I have included, mentions that God sets aside this very day to be a day of crying for the future because we cried for no reason in fear after the negative report. God says that He will give us a good reason to cry. (other items on this piece from the talmud page are the reason why Tisha B'Av was determined to be the date of the Destruction against seeming contradictions in the Bible, which are determined not to actually contradict.)

They do have a lot in common, in five major prohibitions: abstaining from eating/drinking, washing, anointing/using lotions or perfumes, marital (kal v'chomer extramarital) relations (literally translates as "making use of the bed"), and wearing leather shoes (the hebrew word being sandal. Yom Kippur is a Yom Tov, and is the only one on which one cannot cook (it shares the same prohibitions of Shabbat). Tisha B'Av on the other hand, one is permitted to engage in their work. This is one of the reasons I find Tisha B'Av more difficult than Yom Kippur. On Yom Kippur, one is typically at the synagogue (which is usually air-conditioned) all day. On Tisha B'Av you're probably outside a lot and it tends to be one of the nastiest, hottest days of the year. Yom Kippur contains the most beautiful and elaborate melodies, whereas most people refuse to use ANY melodies, including normal weekday melodies, and will SAY the prayers in a monotone on Tisha B'Av. For the only day of the year, the lay-person wears their tallit at every single service of Yom Kippur. Tisha B'Av is the one day of the year where we do not don the Tallit in the morning (usually the only time the congregation wears a tallis... and tefillin) (the wearing of Tallis and Tfillin on Tisha B'Av is postponed to the afternoon, and is the only time where we wear Tfillin in the afternoon... well, unless you accidentially missed Shacharit and do a compensatory service). Tisha B'Av is not just a regular fast day as all the minor fasts are, which commemorate something or other on the path to destruction. Tisha B'Av is the actual day of mourning. We have the prohibitions of a Yom Kippur fast (minus Yom Tov prohibitions) AND the prohibitions of mourning, on which there is considerable overlap and we take bits and pieces of both to make the laws of the Fast of the Ninth of Av. A mourner sitting shiva (seven days after burial) is obviously allowed to eat and drink. They'd die if it was forbidden for seven days! However, a mourner does not don leather shoes, bathe, have sex, or 'annoint'. Additionally a mourner sits on the ground or a low stool (which we observe on Tisha B'Av until mid-day). We do leave our houses on Tisha B'Av, something which is generally forbidden to a mourner from the time they get home (or whereever they will be to sit shiva) after the funeral and burial to an hour into the seventh day (with the exception of Shabbat when they are commanded to attend the synagogue (there are more specifics, but the laws of mourning are way too complex to be discussed in this limited scope and forum). Even mourners sitting shiva are allowed to eat meat (there's ALWAYS deli at a shiva call!), but for 9 1/2 days we cannot. Like people sitting shiva, on Tisha B'Av we are forbidden to study Torah for pleasure (the only other time we are ever forbidden to do this is when we are sitting Shiva, which is what we are basically doing on Tisha B'Av, and there are only a few things we are allowed to study (besides the mandated readings for the day that we read in services, which are the only things we actually read with a melody): Lamentations, Job, Parts of Jeremiah, Certain parts of the Babylonian Talmud: Parts of Gittin and Taanit (which deal with the Midrash relating to Tisha B'Av, and parts of Moed Katan that relate to the laws of Mourning. I also used some parts of the Shulchan Aruch (specifically with the Mishna Brurah) that related to Tisha B'Av, containing obscure customs such as walking home from shul by walking on gravestones This must be a surface reading, no in-depth study is permitted as it may cause joy (though last year I used these texts for the campers to write skits about them).

Speaking of camp, it is usually one of the most memorable experiences at camp and according to former Chancellor of JTS, Rabbi Ismar Schorsch, in an excellent series of Podcasts (type in "What is Judaism" in the iTunes store for a free download. It is entitled "Tish B'Av" [sic].), Camp Ramah saved Tisha B'Av, as if it weren't for Camp emphasizing this so much (not only the day, but you also notice that you haven't been served any meat for nine days and you might inquire why the camp's gone vegetarian) as this is the only holiday celebrated at camp (Ramah Darom people might argue this fact with me when they celebrated Shavuot last year because their camp started crazy-early in late May) and so they hype it up. This may sound sinful, but I actually enjoyed Tisha B'Av at camp. There is so much camraderie in encouraging and helping others to carry out their fast. One year I had campers who had recently been Bar Mitzvahed and this was their first offical fast (because people tend to ignore the "minor" ones) and they were supporting each other (I should point out that fasting is optional at camp and meals are served as normal). I was a member of something I dubbed "The Break-Fast Club", an elite people who attended a second dinner after the fast concluded to actually break their fast. At Ramah Poconos I was a member of the Choir of Death and Destruction where we sang somber Jewish songs about... death and destruction (such an awesome name... in Hebrew we should call it , מקהלת המוות, it sounds good) and we had fun with it. I have fun with a lot of things, as anyone who has ever witnessed me performing Chapter 4 of Megillat Esther on Purim should be able to attest (with my fake crying, for example). I read Chapter 3 of Lamentations a couple of years ago at camp and a female counsellor came up to me and said that they could listen to me do that all night. I honestly didn't know whether to take that as a flattering complement or to be very worried of how morbid that would be. As many of my Jewish (and practicing) vegetarian friends point out, it's great to never have to worry that you're fleyshig (you know, unless someone neglects to tell you the vegetarian dumplings had meat in them, as happened to some of my peeps in Israel). I concur, though as a Kosher Karnivore [SIC (for alliterative effect)] I miss the meat, it's kind of nice to be able to have milchigs whenever I want. "Milchigs"? Whoa, that just sounded really Yeshivish!)

I don’t want to go into all the bad stuff that happens on Tisha B’Av as it can be easily found on wikipedia. I would like to point out a fact that I contributed to the Wikipedia English entry on Tisha B’Av, and that is that the eve of the Disengagement, the final day for most Jews in Gaza and parts of Samaria, was on Tisha B’Av 5765/2005, the expulsion that many compare to the exiles that were caused by the Destruction of the First and Second Temples on Tisha B’Avs so many years ago. Many of the soldiers were heartbroken that they had to forcefully remove our fellow people from our land and empathized and cried with them.

This year too, we are in a dire straits. Though the gates of heaven are closed, we must pray and support the IDF and the actions of Israel, because as Sinat Chinam (causeless hatred) destroyed the Temple, only Ahavat Chinam, (causeless love) can rebuild it.

According to Babylonian Talmud Tractate Taanit 30b, "Those who mourn for Jerusalem will merit to see her in her joy". May this Tisha B’Av be the one of our Redemption and may we no longer need to mourn.

For further reading, besides the wikipedia stuff, I also suggest aish's coverage.

No comments:

Post a Comment